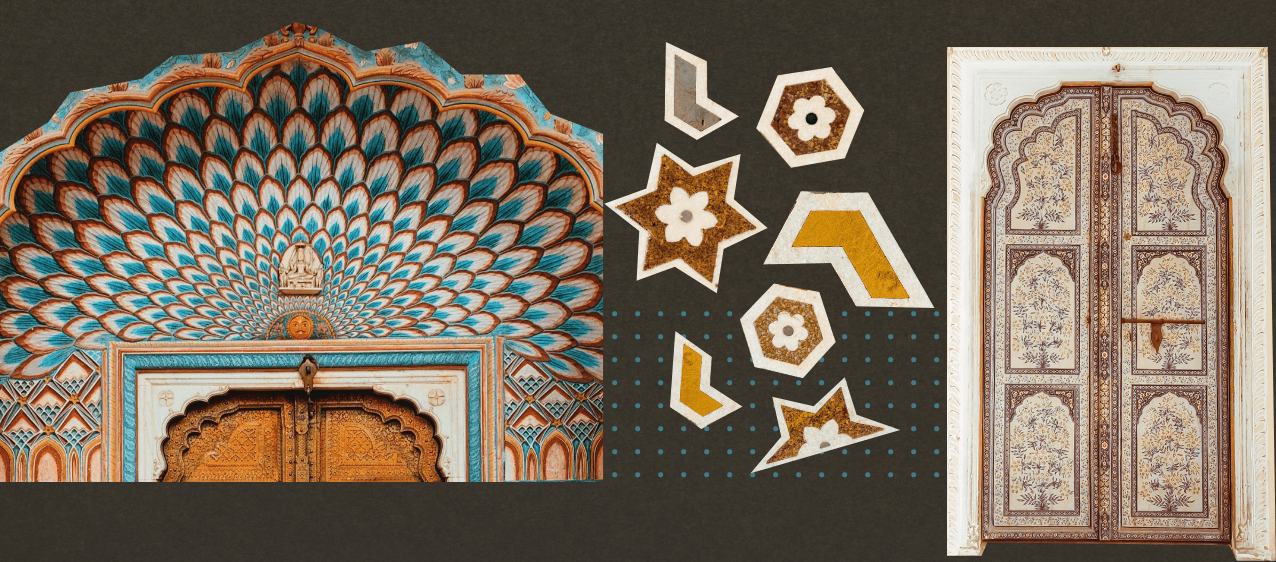

Visual Semblance at the Mughal Court: Inspirations from Design & History

Think flowers and your mind will immediately picture a garden/ a field/ a vase full of colourful, fresh, and blooming flowers. Think Flower Design and your brain might associate further with a pattern you noticed on a textile, a table, a building, or perhaps even an abstract one in a painting. Visual patterns exist everywhere and so does our tendency to notice them consciously and unconsciously. It often almost immediately elicits very personal memories, emotions, and responses. We find ourselves smiling looking at certain paintings, clicking a photograph of random nooks, and what really is that inexplicable urge (in a museum or elsewhere) to run our finger over a mural?

Visual stimulus undoubtedly affects us whether it is placed in our immediate environs or received digitally.

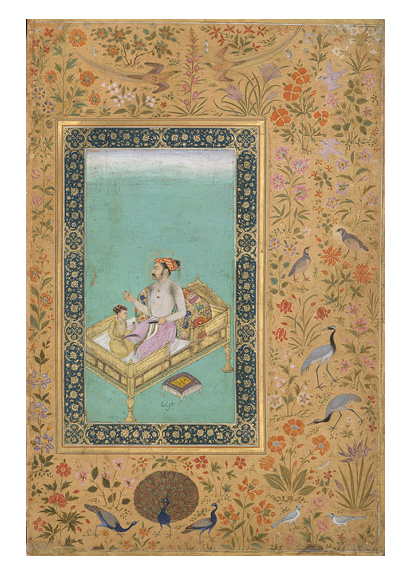

History is a testament to how far (quite literally in miles) patrons, emperors, and artists have gone to capture something that has greatly ‘moved’ them. European herbalists are one such example, alas at times only to keep such resplendent arts hung in their drawing-room. Closer to home, Jehangir (the fourth Mughal Emperor of the Indian subcontinent) made his favourite court artist, Ustad Mansur travel with him often to the various parts of the empire only for poor Mansur to render hundreds of portraits of ‘exotic birds and animals’. Famously, there also exists a very meticulously drawn turkey from North America in the Mughal Royal albums.

In this expedition to Kashmir, Jehangir also tells the Ustad to render hundreds of flowers that he sees there. These flowers inspired by Kashmir’s exceptional flora are no ordinary flowers. Their style seems to be derived from the flowering plants that feature in the base of the Iranian paintings or from the illustrations of European herbals. This style has developed a unique and recognisable identity for itself, so much so that they have come to be known by the Artist’s name, as the “Mansur Flower”. The flowers bowing downwards and emerging from a single parent stem.

Over the 17th century, during Jehangir’s and his successor Shah Jahan’s reign this Mansur flower is observed to be increasingly and obsessively adapted as a decorative motif. It can be seen illustrated in paintings, carpets, on pan-daans, huqqa base, and on buildings like the Taj Mahal and even in the margins of albums.

Similarly, an impulse that today most of us recognise and consciously design is logos. Much like royal Insignias logos serve the purpose of brand identification and are an integral (if not the most integral) part of the brand. Logos like leitmotifs are used across the various components of branding to provide standardization. A concept that Mughals seemed to have known well.

Seen independently placed somewhere one may ponder over the use of a particular design element and what it may represent. In the Mughals’ case the Emperor’s it was the incessant urge to surround the space with the leitmotif of the flower. This is where one observes the other elements and recurring patterns that the distinct Mughal design language was building. From the Taj Mahal to Humayun’s Tomb, one may simply glance to recognise the Char Bagh (Quadilaterial Gardens) with water walkways, the inlay work, the jalis, geometrical design patterns, and recurring building materials to see the visual semblance in Mughal aesthetics.

Further identification of popular motifs and their symbolism, has also been commented on:

“The flowering plants painted in gold and polychrome on the borders of his manuscripts are similar to those woven on carpets or embroidered on robes. Everything is rigorously symmetrical and perfectly balanced, presenting a world of complete harmony, on earthly paradise in which the ugly reality of poverty had no place.”

To put it succinctly, it is an environment built around the central concept of paradisiacal imagery. A postulation that the Mughals wished to communicate culturally and socially to the citizens of the Mughal World and the generations to come of which they were the elite.

Apart from its connection to Mughal royalty, the flower with its associations with abundance and paradisical connotations lends itself suitably to a design that wishes to captivate an audience with reflections of India’s glorious past and provide services ‘fit for a king or queen’.

A flower, inspired from the floral spectacle of Kashmir is strewn across monuments in the plains of the Indian Subcontinent. The flower-infused buildings in the plains, represent splendour even in the hottest and most ordinary of environs like Delhi. Even today if we were to see the flower painted on a wall or printed on paper it elicits an association to lavishness with its sheer colour and form. Its distinctive qualities are retained around motifs and patterns that grow more abstract and more minimal. Walking in the compound of the Taj Mahal observing the inlay and relief of the ‘Mansur Flower’ is a continuing testament to that feeling of alluring enchantment that one discovers. A memorable aesthetic imprinted in the minds of a global audience.

Now centuries apart when the design language has changed tremendously, it is worth imagining how this contextually drenched Mansur flower can become a source of inspiration for contemporary design. With its roots deeply entrenched in royal and paradisiacal metaphors, the flower seems to possess virtuous qualities. Qualities of opulence and grandiosity that many brands may resound with.